Project title: Research project on current forest status, international cooperation, strategic development plan, and best forest management practices in Greater Central Asia Region [2016P3-GCA]

Supervisory agency: State Forest Administration of China

Executing agency: APFNet

Total budget (all from APFNet): USD 42,857

Duration: January–December 2016

Target economies: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan,Mongolia, China

Objectives: Develop integrated research on forestry legislation and governance, mid- and long-term forest development plans, forest management status, forest development needs, constraints and trends, and international forest cooperation in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Mongolia, and China; Under the “Belt and Road Initiative” and the China-Mongolia-Russia strategic economic framework, develop and propose international forestry cooperation mechanisms between China and other economies in the Greater Central Asia (GCA) region; Based on lessons learned on desertification control, forest fire prevention, forest pest control, biodiversity conservation, and degraded land restoration from GCA economies, summarize the best practices for sustainable forest development, technical support and cooperation among forest businesses in the future.

Expected outputs: Six reports on forest development and best practices of forest management in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Mongolia, in both English and Chinese, outlining (1) current state of forests and forestry, (2) contribution of forests to economic development, (3) forest policy and legislation, (4) best practices for sustainable forest management, covering topics on soil and water conservation, desertification control, forest fires and pest control, salinization, biodiversity conservation, rehabilitation of degraded forests, comprehensive utilization of forest resources and non-timber forest products, (5) forestry education and research, (6) forestry projects and initiatives, and (7) international forestry cooperation mechanisms; Publications in Chinese journals; Hold two technical meetings.

Project background

The Greater Central Asia (GCA) region encompasses Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and western China. The region harbours unique ecosystems and biodiversity but very low forest cover and strong pressures on forests, including overgrazing, high fuelwood demand and illegal logging. Many forests have been destroyed or degraded, leading to a demand for forest rehabilitation and restoration. APFNet identified the GCA region as one of its geographical priority areas for strategic interventions but undertaking comprehensive forest research and forest management is difficult given the lack of precise and consistent forest data. Moreover, weak forest legislation, governance and lack of rights to private land ownership, plus the strong focus on industrial development reduce the incentive for sustainable forest management. In 2016, APFNet conducted this research project to gather information, undertake analysis and identify best practices of forest management in the GCA region to share with relevant policymakers and the international community. APFNet invited government officials and experts from forestry authorities in six GCA economies, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, to discuss forestry legislation and governance, strategic development plans, forest education and research, and international forest cooperation. Following consultations, desk research and field surveys, a holistic overview of the current state of forests and forestry; contribution of forests to economic development; forestry policies and legislation; and forest education and research in each GCA economy was published. Each report identified best practices of sustainable forest management, addressing soil and water conservation, desertification control, forest fires and pest control, biodiversity conservation, rehabilitation of degraded forests, and utilization of forest resources and non-timber forest products. The reports also provide important sources for the development of international forestry cooperation and commitments for climate change adaptation, biodiversity conservation, and desertification control, etc. Each GCA economy is actively involved in many international and regional commitments, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), United Nations Forum on Forests (UNFF), UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) and the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

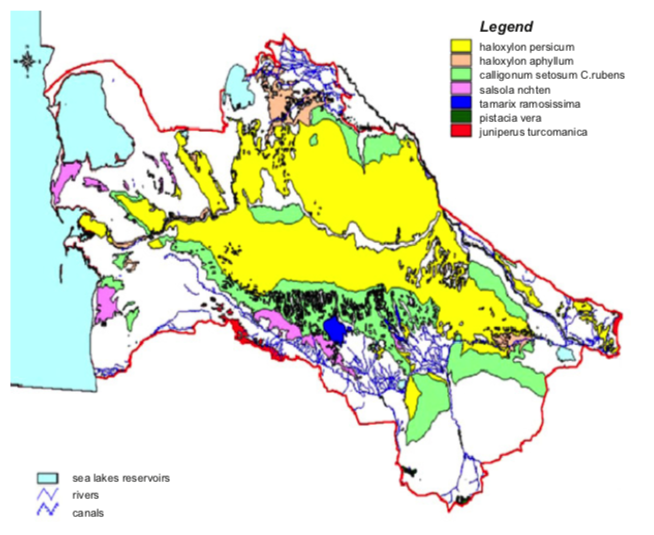

Figure 1. Forest map of Central Asia

Source: FLERMONECA and Regional Environmental Centre for Central Asia, Environmental Agency of Austria, Zoї Environment Network, 2015. The State of the Environment in Central Asia, https://zoinet.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/SOE-regional-eng.pdf

Under the context of accelerating globalization and economic recovery of the GCA economies after the collapse of Soviet Union, China has emerged as one of the most important players and largest investor in the GCA region under the “Belt and Road Initiative” proposed by Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2013. Since then, China has enhanced cooperation with GCA economies both bilaterally and multilaterally.

Project featured topics

Pressures on forest management in Greater Central Asia

The region has a harsh climate and both mountains and deserts. Most economies are landlocked and classified as low to middle income by the World Bank. Since the fall of the Soviet Union and independence for all economies in 1991, forestry policy has transitioned from meeting the demand for raw wood or agricultural needs to privatization of property. Given this recent shared history, legislation and governance in the forestry sector and sustainable forest management practices in GCA economies share many similarities. All economies have very low forest cover and strong human pressures on forests, including overgrazing, high fuelwood demand and illegal logging. All forests in the GCA economies are publicly owned but there is a rapid transition towards privatization of property. Over the years, governments have approved a number of medium to long-term programmes, ranging from three to 15 years, to protect forest resources or undertake reforestation, afforestation, artificial breeding and forest design. Most funding for forest management comes from central government budgets due to limited opportunities for regional or local organizations, such as farmers’ associations, rural communities, non-government organizations, educational and research institutions, to generate revenue from forest-related activities. Given the low forest cover and policy visibility of forest issues, most forest management units in GCA economies are underequipped and underfunded, leading to ineffective sustainable forest management. This project has been developed in collaboration with national forestry experts in each economy to provide support to protect and management their forest resources, develop national forest policies and implement best sustainable forest management practices over the long-term.

Identifying best practices for forest management

Working with national experts, the project compiled a report on forestry development and best practices of forest management in each economy, with a focus on the following topics:

1) Current state of forests and forestry in each economy.

2) Contribution of forests to economic development.

3) Introduction to forest governance systems, relevant laws and regulations, and key agencies involved in forestry management.

4) Information on forest management approaches, such as soil and water conservation, desertification control, biodiversity conservation, rehabilitation of degraded forests etc.

5) Forestry education and research systems.

6) International forestry cooperation mechanisms.

7) Future challenges and opportunities for forestry development.

Click below to find summaries of the main ideas from each book:

1. Forestry Development and Best Practices of Forest Management of Kazakhstan

2. Forestry Development and Best Practices of Forest Management in Kyrgyzstan

3. Forestry Development and Best Practices of Forest Management in Tajikistan

4. Forestry Development and Best Practices of Forest Management in Uzbekistan

5. Forestry Development and Best Practices of Forest Management in Turkmenistan

6. Forestry Development and Best Practices of Forest Management in Mongolia

Kazakhstan

The Republic of Kazakhstan is a large landlocked economy with low precipitation and a continental climate that causes large variations in temperature between summer and winter. Kazakhstan has about 13 million ha of forest and other wooded land, less than 5 percent of the total land area. Despite being considered a low forest cover country, there is a wide variety of forest types in Kazakhstan, very unevenly distributed in deserts and semi-deserts, grasslands and mountains. Saxaul forests grow in desert zones, coniferous forests in the mountains and birch and aspen forests are in the plains of the steppe and forest steppe zones.

♦ Forest development: From 2010 to 2015, up to 283,200 ha were reforested, including 114,300 ha of planted forests, 124,600 ha of planted saxaul in the southern regions, and 44,300 ha of natural forest regeneration. Every year, the economy celebrates “Republic Day of Forest Planning”, attended by environmental agencies, forest owners, national and private companies and youth organizations to plant 1,000,000 trees and shrubs. Forests are recognized as an important source of “public goods”, providing protective functions, such as erosion control and watershed protection along the banks of rivers, lakes, reservoirs and other waterbodies of scientific importance. Valuable forest areas are identified such as forest fruit plantations, state protective forest strips, urban forests and forest parks, green areas of settlements, and forests fulfilling therapeutic roles. However, in the assessment of the economic role of Kazakhstan’s forests, all these functions are not taken into account. The contribution of natural forests to the economy is estimated to be within the range of only 0.01–0.02 percent of the economy’s GDP.

♦ Governance: In accordance with decentralization policies and the constitution of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the economy has a two-tier system of forest management. At the national level, forests are managed by the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan through its central executive body – the Committee of Forestry and Wildlife, Ministry of Agriculture. At the regional level, control is executed by local forest institutions with services and offices for the protection, care and regeneration of forests. Forestry management is funded by three sources: state budgets, paid services by local forest institutions (from the sale of forest goods and wood products, cultivation of plantings), and international organizations for projects on forest and biodiversity conservation. Community-based forestry management is not undertaken in Kazakhstan due to the absence of relevant rules and regulations in current forest legislation.

♦ Forest management approaches: Afforestation and reforestation in the catchments of mountainous areas will address land degradation and water scarcity in Kazakhstan. Riparian buffers along rivers and other inland bodies of water were planted to restore and strengthen the protection of riparian and floodplain forests against erosion. An integrated approach to protect and restore degraded agricultural land is being considered, involving a system of protective plantings on agricultural lands. There is a gradual increase of agroforestry sites in Kazakhstan. The Kazakh Research Institute of Forestry and Agroforestry carried out scientific research to improve principles of agroforestry zoning, including the allocation of 26 agroforestry districts and 15 sub-districts in the forest-steppe, steppe and semi-desert areas. A list of species were developed, as well as technology to assist with propagation and maintenance of shelter belts. To preserve forests, the Government of Kazakhstan has banned the export of all kinds of timber and logging in coniferous and saxaul plantations. At present, the underdeveloped forest industry is focused on primary processing of timber for industrial uses, maximizing the use of small-scale wood, and expansion of industrial plantations for building and construction products.

♦ Education and research: Some educational institutions and training programmes on forestry management and planning do not always meet modern standards, which are reflected in the quality of forestry training. In a number of higher education institutions, only one to ten students are enrolled due to poor student recruitment and retention. The existing system of training forest specialists requires improvement in the quality of training materials and teaching staff.

♦ International cooperation: Within the strategic partnership framework of the GCA economies, Kazakhstan’s most promising areas of cooperation are monitoring of forests, prevention of forest fires, pests and diseases, as well as the establishment of cross-border protected areas for biodiversity conservation.

Kyrgyzstan

The Kyrgyz Republic is located in the east of Central Asia, with an economy dependent on agriculture. Forest cover is only 5 percent, partly due to the difficult climatic and physical conditions in mountainous areas. There are four major forest types in Kyrgyzstan, including nuciferous (walnut and fruit-bearing), spruce, juniper and riparian forests. Forests of Kyrgyzstan provide a very wide range of goods and services, including wood (mostly for energy); walnuts, pistachio, almonds and berries for sale; grazing for meat and dairy; shade and local climate control; water supply and protection against erosion; and tourism. However, forestry is not a key sector in the Kyrgyz Republic and the gross output of forestry is only 1.24 percent of GDP.

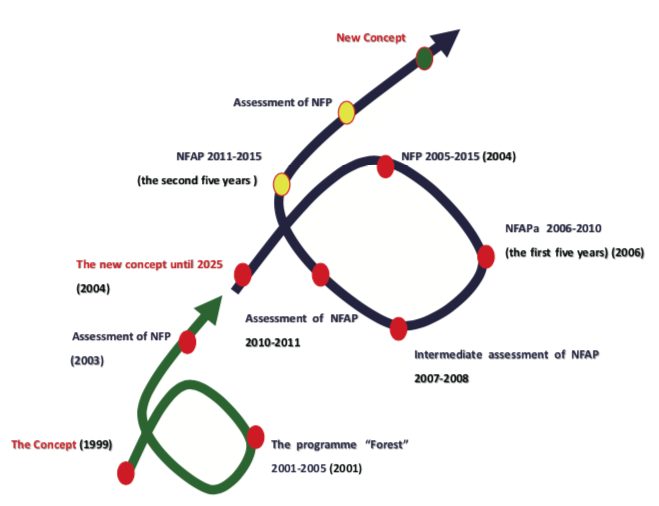

♦ Forest development and governance: Forest management in this economy presents a vertical institutional structure. All forest ownership and rights in Kyrgyzstan are in the hands of the state, specifically the State Agency of Environment Protection and Forestry. Regional forestry institutions are responsible for the monitoring of forest management, while at the local level, forest enterprises work with local communities to harvest timber and other forest resources using community forest management plans. The transition to democracy and a market economy created the need for forest policy reform in Kyrgyzstan. Figure 2 illustrates the spiral development of the national forestry policy of Kyrgyzstan. Transition between spirals is dependent on assessment of implementation of the planned arrangements and determination of new emerging principles. Currently, the policy is on the second cycle of its development.

Figure 2. Development of national forest policy 1999–2015. Red circles represent completed stages of development.

The National Forest Programme (NFP) and National Forest Action Plan (NFAP) are two key elements of national forest policy in Kyrgyzstan, which is based on the three components, namely “Forest, Humans, Government”. NFP is a medium-term programme that determines the complex arrangements and measures to implement forest development. NFAP is a short-term plan of activities that contribute to the implementation of the NFP.

♦ Forest management approaches: Reforestation and afforestation activities include seed preparation, growth of planting material, planting seedlings and general aid in reforestation. Community forest management (CFM) is a new form of forestry management in Kyrgyzstan. During the first decade of its implementation, CFM was actively pursued and implemented by communities, particularly in the planting of walnut forests. However, the number of CFM members has been declining since 2013. Today, there are only 131 CFM members renting land and walnut forests are being replaced by many forest farms. Intensive use of forest resources in Kyrgyzstan led to an abrupt destabilization of forest ecosystems and widespread decline in forest health, including major damage by insects and other diseases. For example, mature Spruce tianshanica are affected by rot and vulnerable to insect attack. This is the main reason for the decline of quality and value of timber.

♦ Education and research: Technical capacity of forestry authorities is weak and equipment for carrying out forest protection, reforestation and afforestation has not been updated for 20 years. The Forest Institute of the National Academy of Sciences carries out basic and applied forestry research to provide a scientific basis for conservation, reforestation, sustainable forest management and expansion of forest areas. Despite the potential of the institute’s work, the Government of Kyrgyzstan does not provide any funding for scientific research, with the result that new studies have not been carried out for the last 10–15 years. Laboratories need updated equipment including computer technologies. Employees in the forestry sector also need to increase their professional skills and participate in research.

♦ Challenges: Future challenges in the forest sector in Kyrgyzstan include reducing forest degradation due to grazing and fuelwood consumption, increasing areas protected by forests through afforestation, improving the livelihoods of forest-dependent people and reducing bureaucracy to support individual and local initiatives.

Tajikistan

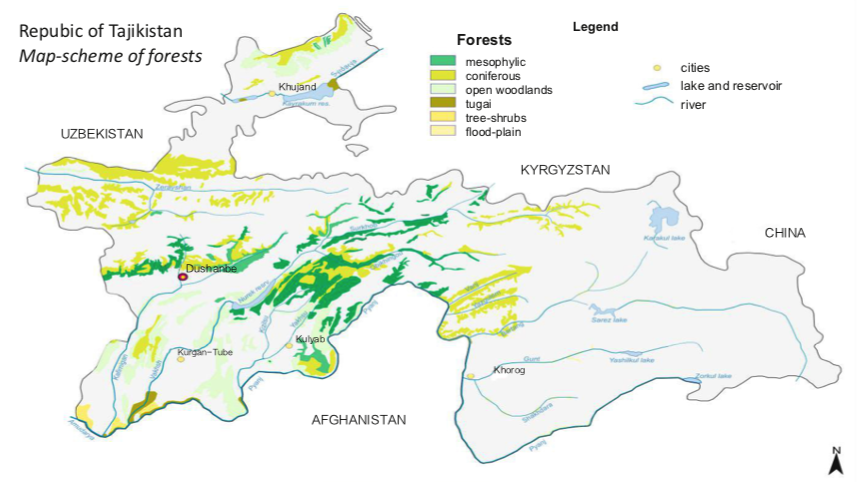

The Republic of Tajikistan is a landlocked economy with over 93 percent of the territory mountainous. With about half of the territory higher than 3,000 m in altitude, Tajikistan is prone to frequent natural disasters and has highly vulnerable ecosystems. Although Tajikistan is a sparsely wooded economy, the role of forest resources is particularly important in connection with global climatic changes and social transformations in the economy. Only 3 percent of Tajikistan’s territory is covered by forest plantations, and about 500,000 ha of state forest lands are currently used as pastures. Around 70 percent of the rural population is directly dependent on natural resources. Forest plantations have important environmental functions including protecting mountain slopes from erosion, landslides and other natural disasters, and forming water catchments for transboundary rivers such as the Amudarya and Syrdarya. However, a national forest inventory in Tajikistan is difficult due to the lack of reliable, accurate and updated data on forest resources.

Figure 3. Map of forests in the Republic of Tajikistan

♦ Forest development and governance: Most forest in Tajikistan is under the responsibility of the Forestry Agency, which directly answers to the government. The Forestry Agency sets national policy and targets and provides technical advice, while management is carried out by local forest management enterprises. Strategies for the development of forestry in the Republic of Tajikistan lay out specific priorities: 1) forest management mostly concerns the protective functions of forests and excludes timber extraction; 2) harvesting and processing of non-timber forest products are emphasized; 3) leasing contracts with private organizations are permitted; 4) scientific forest research institutions focus on juniper forest cultivation, selection of nuts, wildlife monitoring, and the biology of common forest pests. All forests of Tajikistan are classified as protection forests of environmental, economic and social importance, since the majority are located in the mountains and perform protective, anti-erosion, soil and water-regulating functions.

♦ Forest management approaches: In accordance with the forestry development programme 2006–2015, reforestation was included in the first priority of the development of forestry in Tajikistan and over 10,000 ha of forests have been established to improve forest protective capacity and the environment. A national forest strategic development plan aims to improve the capacity of forest institutions to implement sustainable forest management (SFM) in Tajikistan. All SFM practices are beneficial not only for the forest resources of Tajikistan, but for rural livelihoods and employment, as these practices reduce extreme poverty of forest-dependent people, improve rural energy supply, limit soil erosion and contribute to climate change mitigation.

Figure 4. Afforestation and reforestation of Tajikistan. Photo: APFNet

Legal property rights of farmers and tenants are usually long-term or lifelong, based on a land certificate or lease terms, which assists community forest management. The main sources of firewood are private domestic gardens, particularly those that cover large areas and provide an opportunity for residents to plant more woody vegetation to meet their fuelwood needs without any additional costs. Forests and woodlands are economically important to a significant proportion of the population, particularly those living in mountain villages. The main sources of income are from livestock, horticulture, agriculture and beekeeping.

♦ Education and research: Currently, one-third of forestry employees have secondary or incomplete secondary education. The numbers of employees with a specialized secondary or higher education qualifications is not sufficient to meet the demand for forestry professional staff. The only forestry training programme is offered by the Horticulture and Agricultural Biotechnology Department in the Tajik Agrarian University, in which up to 25 students are enrolled per year. In 1998, 236 people graduated from the Tajik Agrarian University but only 5 percent of graduates are working in the forestry sector. Many of the current employees of the Forestry Agency have graduated from Russian universities, Lvov, Voronezh, Moscow, and St. Petersburg, which were accessible during former Soviet times. After independence in 1991, access to those universities was only reinstated in 2009. There were four Tajik graduates from Russian universities since 2009, but none returned to work in the forest sector.

♦ Future opportunities: Forests in Tajikistan are an important component of the natural resource potential of the economy, to help solve problems of desertification and conservation of biodiversity in the context of global climate change. The economy currently harbours 268 species of trees and shrubs, of which the most species-rich are xerophilous forests with 89 species, small-leaved forests with 57 species, and deciduous forests with 45 species.

Tajikistan also has a rich fauna, which is both the fauna of high Central Asia, such as Tibet and the Himalayas, and the fauna of deserts and steppes of Central Asia. In Tajikistan there are 49 species of fish, 2 species of amphibians, 47 species of reptiles, and 82 species of mammals.

Uzbekistan

The Republic of Uzbekistan is a dry, double-landlocked economy in Central Asia, one of only two “double-landlocked” economies in the world. Forests in Uzbekistan are categorized as mountain, valley, floodplain (tugai) and desert forests and cover about 7 percent of the total territory.

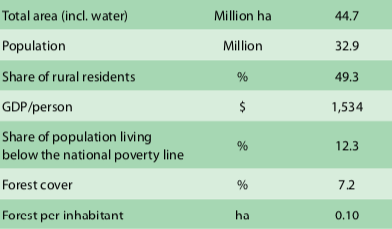

Table 1. Uzbekistan in context, 2015.

Source: United Nations (UNECE) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2019. State of Forests of the Caucasus and Central Asia. https://unece.org/DAM/timber/publications/sp-47-soccaf-en.pdf

A large part of Uzbekistan is highly susceptible to land degradation and desertification. The most serious environmental problems threatening the economy’s natural resources include increasing soil salinization and water pollution, wind and water erosion, overgrazing, deforestation and loss of biodiversity. Therefore, the main function of forests in Uzbekistan is protection against further environmental damage.

♦ Forest development and governance: Practices for sustainable forest management focus on combating desertification, preventing erosion, as well as protecting irrigated agricultural land and pastures from degradation. The development of forestry has a significant positive impact on other sectors of the national economy, such as agriculture, livestock and water conservation. The priorities for forestry development in the economy are protecting existing forests from degradation, pressures from grazing and excessive fuelwood harvesting. Development of social forestry, i.e. management of forests for the benefit of local communities using best practices and learning from experience in the changing development environment is also a priority.

In Uzbekistan, forest policy and implementation of forest-related activities are under the responsibility of the Main Forestry Department (MFD), which manages forests at the regional level and directly answers to the Ministry of Agriculture and Water Resources. To meet Uzbekistan’s timber needs, from 2010–2014 MFD established fast-growing species (i.e. poplars) plantations that can produce up to 500 m3 of timber per ha from twenty-year pilot plots. Over 80 percent of the total reforestation, including forest plantings, were planted in desert areas to combat desertification. Forming protective forest belts in desert zones halts moving sands and stabilizes the soil; thus 1 ha of saxaul plantations prevent the transfer of 30 tons of sand per year and provide favourable conditions for flora and fauna.

In the desert lands, MFD undertakes three main forest reclamation activities: 1) establishing a system of protective forest belts; 2) planting around large irrigation and main road networks; 3) fixing moving sands and sand forestation through planting saxaul and other sandy species. Fixing soils of the exposed bed of the Aral Sea is also done through forest planting, at a rate of 15,000–16,000 ha of forests per year. The total amount of forests planted by MFD each year in Uzbekistan is 42,000 ha.

♦ Education and research: Adequate technical and financial support for training forestry staff is not available. Moreover, there is a lack of forestry professionals and experts who are able to guide technical decision-making in both central and local forest management.

♦ International cooperation: A number of international organizations have implemented projects on biodiversity conservation and promotion of community-based forestry activities. For example, a United Nations Development Programme/Global Environmental Facility project has a component focused on community-based forestry and afforestation. This included the development of methodological guidelines, training, selection of pilot sites, development and adoption of legal and regulatory documentation on long-term forestland leases, and implementation of reforestation activities at pilot sites. As a signatory to a number of international environment conventions, Uzbekistan fulfills the required reporting commitments and obligations for UNCCD, CBD, Convention on the International Trade on Endangered Species (CITES), Ramsar, UNFF, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization Committee on Forestry, International Forum on Forests and Intergovernmental Panel on Forests.

♦ Future opportunities: Although forests and trees cover just a very limited part of Uzbekistan’s territory, forest ecosystems can significantly contribute to the welfare and livelihoods of a substantial part of the rural population. Contributions could be both direct (e.g., timber and firewood, non-timber, etc.) and indirect (e.g. fixing moving sands, rehabilitation of degraded pastures, establishing protective forest belts and forest nurseries to grow planting stock).

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan is the second-largest economy among the six Central Asian economies, and its forests grow in difficult climatic conditions. It is a low forest cover economy with only 4,127,000 ha of forests, covering 8 percent of the total land area. There are three main types of forests; mountain forest, desert forest and riparian forest.

Figure 5. Forest cover map of Turkmenistan

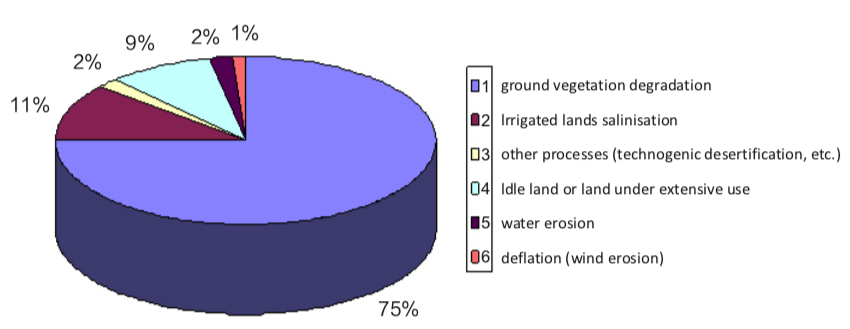

About 75 percent of land degradation directly relates to the loss of ground vegetation mainly due to human factors (fuelwood collection, overgrazing and fire). Climatic conditions, especially in drylands, are also a factor when consecutive dry years cause a reduction of ground cover vegetation biomass.

Figure 6. Land degradation forms in Turkmenistan

♦ Forest management approaches: Sustainable forest management is a long-term process, especially in the exceptionally dry and harsh continental climate of Turkmenistan. Consumption of forest products per head is extremely low, and there is now no local production of timber and firewood at all. All forest products must be imported. Financing for forest management is provided by ministries and all afforestation activities are carried out in accordance with the National Forestry Program which specifies the activities, participants, and responsible organizations. Only people in remote villages use forests for firewood. Firewood can only be collected by special permission from the Forestry Administration, who specify the volume limits and collection area. In forest areas, only sanitary cutting is allowed, while commercial production of wood is not practised because there is insufficient timber available.

In Turkmenistan, it has become a tradition to plant deciduous, coniferous and fruit bearing trees, and there are about 3 million trees planted every year. The municipality employees of the capital Ashgabat, ministries and branch departments are tasked to plant 1.5 million trees between the towns of Anew and Baharly and 20 percent of these are fruit-bearing trees and grapes. Community forest management in Turkmenistan is limited to growing fruit trees or gardens in small-sized plots. People grow fruits and nuts primarily for their own needs and sell the remainder in markets. According to the Forest Code of Turkmenistan, forestlands can be leased either with a short-term lease for five years or a long-term lease for 50 years.

♦ Education and research: Turkmenistan places a special importance on developing forestry management research and send professional staff to be trained at educational institutions abroad. Research areas included techniques for growing plants resistant to saline soils for the restoration of pasture areas, combating pests and rodents, or development of technologies for the preparation of juniper seeding and growing saplings. However, the technical equipment of forestry departments in Turkmenistan is insufficient. The lack of transport and communication systems result in poor patrolling of forest territories.

♦ Future opportunities: Afforestation and reforestation activities in Turkmenistan focus on planting drought-and salt-tolerant species adapted to local conditions. Restoring degraded wooded areas and protection of biodiversity is a growing trend in the economy’s forest sector policies.

Mongolia

Located in the heart of Central Asia and landlocked between Siberia and China, Mongolia is one of the world’s highest-altitude economies with 81 percent of its territory over 1,000 m above the sea level. The total forest cover in Mongolia is 17.5 million ha. Mongolian forests are divided into two distinct regions: the northern boreal forests and the southern saxaul forests in the arid desert regions. Most forests in Mongolia are larch forests (Siberian larch, Larix sibirica Ldb.), covering about 59 percent of the northern forest area. Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and Siberian pine (Pinus sibirica) are also important, covering over 5 percent and almost 8 percent respectively. Birches (Betula platyphylla, white birch, mainly) cover almost 9 percent. In general, Mongolian forests have low productivity and growth due to extremely cold, harsh winters and low precipitation, and they are vulnerable to disturbance from drought, fire and pests.

♦ Forest development and management: Forestry development in Mongolia is largely dominated by the public sector. There are several key areas of legislation on forests, protected areas, land and mining, however, interlinkages between laws on mining, environmental protection and forest management are poor. Moreover, limited implementation and enforcement capacities of national institutions are another challenge. The Mongolian Government implemented the “Green Wall” programme in 2005 to control desertification. Each year, forest shelterbelts are established and replanted in desert and steppe ecosystems. The most critical factor affecting forest resources in Mongolia is wildfire. As mandated by the updated Regulations on Forest Fire Prevention in Forest Law, important forest areas are separated by firebreaks from the most probable direction of the advancing fire. Radio, other communication systems and watchtowers are used for early warnings on fire outbreaks. At present, 15 towers oversee one-third of the economy’s forest areas. Forest roads are constructed and improved to support regular patrolling and awareness-raising activities, and to speed up fire-fighting responses to prevent the spread of fire.

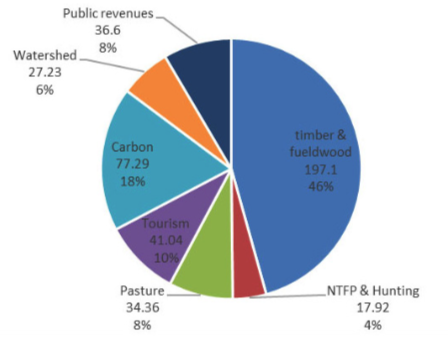

Planting or sowing of desired species such as pine and larch is required to supplement natural regeneration after illegal logging and fire. The share of non-coniferous species such as birch and aspen are increasing, and some areas are turning into grassland. At the end of 2006, the total plantation area was recorded as 117,943 ha but quality of plantations is generally poor and survival rate of seedlings is reported to be in the range of 30–60 percent due to incompatibility of site and species, poor site preparation, poor quality of planting stock and lack of maintenance. Although afforestation initiatives are reported to have increased, there are a number of sources that show an overall decrease in forest area and quality during the last decades, due to hunting, herding and urbanization. The state forest policy proposes that the area of naturally regenerated and planted forests will be increased to 310,000 ha in 2020 and 1.5 million ha in 2030. Assuming about 70 percent of rehabilitation is intended to be achieved through natural regeneration, there is a ‘theoretical’ need for planting 90,000 ha of trees from 2015–2020. The economic and environmental significance of forests in Mongolia can be assessed by the value of goods and services they provide to the economy. Forest goods and services contribute Mongolian tögrög (MNT) 431.54 billion (USD 150 million) to the economy, which is around 3.1 percent of Mongolia’s GDP.

Figure 7. Partial estimate of the economic value of forest goods and services (2013, MNT billion)

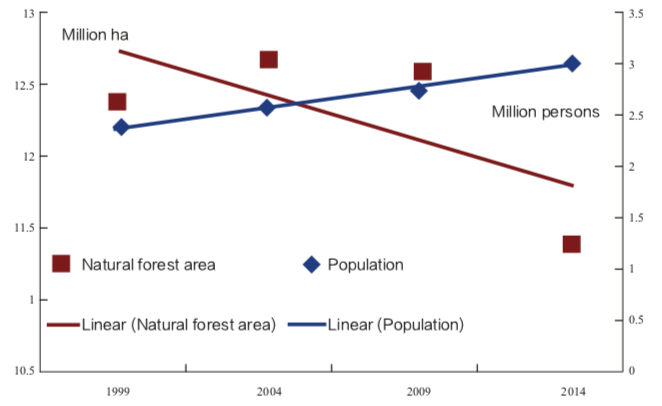

Forest resources represent an important contribution to livelihoods, and changes in the forest sector have grave socioeconomic impacts. As the population has increased over the last decades, forest areas have continued declining at various scales and locations. Forest areas declined mostly around the capital city Ulaanbaatar, but, in rural areas, population growth results in economic growth and an increase of pervasive rural activities such as herding, hunting and gathering, which are all detrimental for forests.

Figure 8. Relationship between forest area and population (1999–2015)

Communities in the forested areas of Mongolia are severely affected by forest degradation. The number of people employed in the forest industry fell from 12,000 to less than 6,000 between 1980–2015. Previously employed by state enterprises, people have either migrated, or resorted to other forms of (temporal) employment or (informal and primitive) logging and small-scale sawmill operations. This has led to an increased level of poverty. Communities rely heavily on fuelwood availability, timber for household use, and wood for the production of traditional products (e.g., Mongolian felt tents). Community forest management was enshrined by the Mongolian Forestry Law in 2007; an important paradigm shift from state forest management during the Soviet-influenced era towards private and community-based forest management. After the law’s enactment, forest resources were allocated to private companies and communities. The Government of Mongolia is now setting in place a variety of mechanisms to provide subsidies and other incentives to forest user groups, including preparation of secondary legislation that will allow payments to be collected for forest use and management. Fees will be based on a percentage of the costs of forest management using a standard cost norm calculated to apply to all forest user groups.

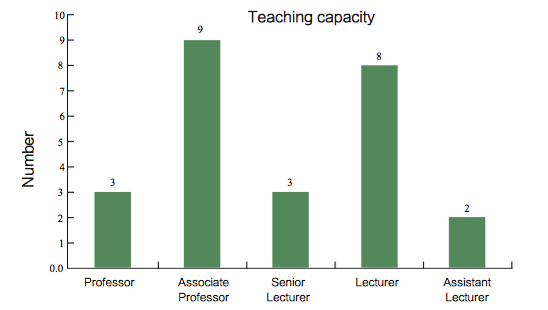

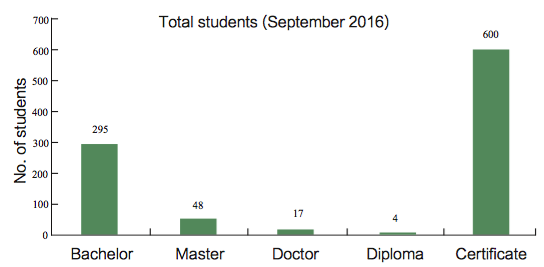

♦ Education and research: Curriculum development remains the highest priority for forestry education institutions and further support from governments, donors and education specialists is needed. During the last 3–5 years, Mongolia has reformed the higher education system, specifically the state-owned universities. Forestry, forest science and forest production have been merged with other natural sciences and become interdisciplinary studies. Current challenges of forestry education include an outdated curriculum design and delivery, lack of networking among universities, and poor inter-linkages between forestry education and industry due to very limited job opportunities. As of 2016, there are five universities offering forestry-related education with 474 undergraduates in the 2005–2006 academic year, 396 in the 2010–2011 academic year, and 371 in the 2015–2016 academic year. Figure 9 shows the forestry teaching capacity in the five universities. There are three full-time forestry professors in Mongolia. Associate professors and lecturers are the most common staff position in all forestry departments.

Figure 9. Number of forestry faculty members in five universities in 2016.

Figure 10. Number of undergraduates studying forestry-related topics in 2016.

Figure 11. Total number of students enrolled in forest-related courses in five universities from 2005–2016.

♦ International cooperation: Mongolia is signatory to several international treaties with important implications for forest management. The most significant include CBD, CITES, UNCCD and UNFCCC. CBD obliges Mongolia to establish a system of representative protected areas. CITES requires the introduction and implementation of measures to regulate the trade of endangered plant and animal species. UNCCD requires local communities and other stakeholders to implement integrated approaches to combat desertification.